Attacks

Pars orationis non est secura: Using parser combinators to detect flaws

Security analyst

Updated

Mar 22, 2018

7 min

We like bWAPP around here, because it’s 'very buggy!'. We have shown here how to find and exploit vulnerabilities like SQL injection, directory traversal, XPath injection, and UNIX command injection. All of these have one thing in common, namely: they could have been prevented with a little Input Validation.

Taking some ideas from static code analysis and the 'code-as-data' approach, what if we could use some sort of code or syntax analysis tool in order to gain intelligence about where an apps’s weaknesses lie? That’s what we use 'parsers' for.

Manual detection

Let us consider, for example, this site in our favorite buggy web app:

Adding an entry to the "blog."

Every time we load the page, the current entries in the blog are SELECTed from a MySQL database.

The source code for such a page is like this:

See here (adapted from bWAPP; braces and loads of lines removed).

We’re mainly interested in the PHP and HTML mixed in the <div id="main">, which is just what we cropped here, because that’s where the SQL is. Looking at a few more sources, we see we always exploit the same weakness:

An SQL query is made up by 'concatenating' literal values, PHP function calls and PHP variables like $entry above. That variable comes from a POST request and passed through the sanitizing function SQLi. After concatenating and building the query, it is sent to the database for processing.

Thus we could type

into the entry field to turn the query into a dangerous, blog-deleting one.

In order to successfully identify these SQL injections, we need to look for strings which contain SQL code, and also use the PHP concatenation (first . last). That’s not enough, because we also need to relate the concatenated variable with the input or parameter where we are going to place the malicious SQL code.

To hunt SQL injections in bWAPP, our tool of choice will be a set of 'parsers', i.e., a piece of software used to scan a string or file to look for parts that conform to a specific set of rules.

Specifying the targets

Before going into parsing and grammar issues, let us first reflect about what we want to find. We want to detect pieces of text in the code that conform to the syntax of an SQL SELECT or INSERT statement. But also they must have concatenations, because a simple statement like

is perfectly safe. Where could we possibly inject anything?

So we need SELECT or INSERT with concatenations. Also, we want our tool to be able to identify

which variable is at risk,

where and how it is defined,

whether or not it is protected by some function

For our purposes, the INSERT statement has this form:

We’ll use subparsers to define what each of these elements mean, v.g., values. But what is a value? Consider this rich example:

A value can thus be:

a fixed number or string,

a

MySQLfunction likeNOW(),a concatenation of a string or number obtained from

a

PHPvariable ($var1) ora

PHPfunction (clean()), which may also take arguments.

This is where parsers shine and the alternative approach, regular expressions, fail. Imagine trying to write a regex to match such an INSERT with concatenations. It would be humongous, not to mention very hard to understand. Other disadvantages of regular expressions are that they have to deal with white space explicitly and are hard to maintain when there are any changes to the language syntax. As the famous saying goes:

Some people, when confronted with a problem, think "I know, I'll use regular expressions." Now they have two problems. —Jamie Zawinski

Learning the parser-tongue

Our weapon of choice will be Python and pyparsing.

You don't need to be a wizard to use pyparsing!

Some nice features about pyparsing:

uses a simple syntax that makes the grammar transparent

fits well in your

Pythoncode,uses standard class constructs and plain language instead of cryptic odd symbols,

is tolerant to change and easy to adapt to different input or targets to match,

includes a few nice helper functions, like parsing actions (v.g. convert a string of digits to an actual integer)

In pyparsing, the outermost parser for the INSERT above translates to:

The functions in SentenceCase are built into pyparsing, and their names are pretty self-explanatory. The + operator is overloaded to mean "followed by".

Take Word to mean any combination of the given characters. Thus sql_identifier is just a combination of alphanumeric characters and the underscore. values is just a delimited list of values, enclosed in parentheses. We Group that list into a single entity so that we may refer to it by name later.

PHP identifiers are like SQL names, but must start with the symbol $. We also define function calls:

Unlike Group, Combine squashes all matched tokens into one. We do that because we don’t really care about every single part of a function call, only the php_identifiers inside, and we can access that by the name with which we baptized PHP identifiers above.

Finally, we get to the heart of the matter: a value to be inserted is either a literal word or number, the result of a function, or a 'dangerous concatenation':

Here ^ is the logical connector or, and we’ve omitted a bunch of Literal parsers for all the quotes and dots. By the way, notice that all these named parts of our big parser are parsers themselves, and we can use them on their own.

One way to use a parser is the parseString method. This will return the structure of tokens, if it is a match, or throw a ParseException if not.

The function scanString looks for substrings that match the grammar. Quite useful. It also tells you where the substring was found. We use it to tell the user the line and column where the potential SQL injection was found:

How to use pyparsing.scanString.

These are just some of the pyparsing built-in helper functions mentioned earlier: scanString returns an iterator which gives tokens, just like parseString(), but also starting and ending 'characters'. To convert them to 'line' and 'column' numbers, we use the functions lineno() and colno(), respectively.

Where parsers actually beat regular expressions is in extracting information and structure from the input, as we did above to identify the inserted values and from those, which are the variables where we can inject SQL. For that, we need to parse again because we don’t know beforehand whether the inserted value is a function call or a PHP identifier:

Remember we need to detect lines with SQL queries that contain dangerously concatenated variables, but also 'where' those variables are taken from user input and whether they are protected. But since we already have the injectable variable as a regular string, we can create 'yet another' parser on-the-fly to find the lines where that variable is mentioned. This one is simple:

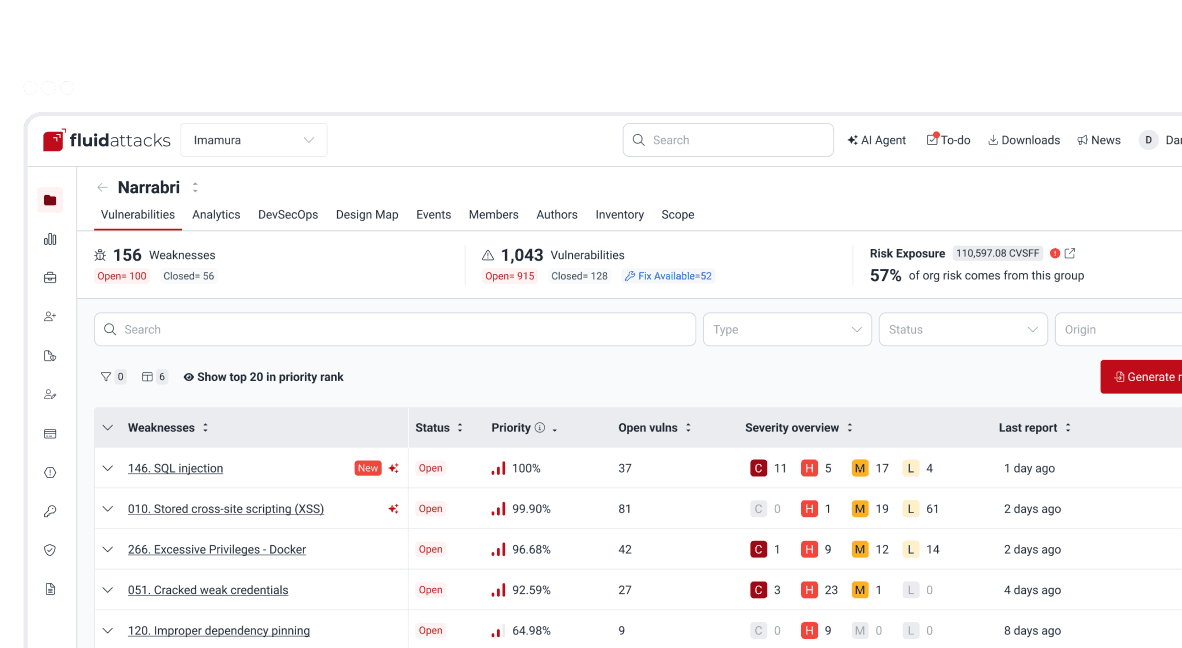

Finally, we run this code for every PHP file in the bWAPP server root. The output we get is very long (see the full report). Here is part of it:

Boy, that’s a load of SQL injections! However, some of these matches might be a 'false positive' and maybe some files have 'escaped' our scrutiny.

To find the ratio of discovered vulnerabilities to existing ones (the 'yield'), consider the 57 SQLi in Netsparker Compared to our 56, that gives us a 'yield' of 98%. Not too shabby for our simple parser. Hence the 'escapes' is 2% in this case.

Given the parser design, and checking the script output, we see that only really dangerous concatenations are reported. Thus, we might say, with a statistically sound 95% confidence, that our pyparsing parser reports zero false positives.

At Fluid Attacks, our ethical hackers review code with manual techniques, yielding results with very low false positive and false negative rates. Do you need help with vulnerability management? Just contact us.

Reference

McGuire, Paul (2008). 'Getting started with pyparsing'. O’Reilly shortcuts.

Appendix: Full SQLi parser

Download the code and test cases. Run from the root of the tested PHP server.

Get started with Fluid Attacks' application security solution right now

Other posts