Attacks

My heart bleeds (but not for you): Understanding the flaw behind Heartbleed

Security analyst

Updated

Apr 25, 2018

5 min

Back in April 2014, one of the biggest vulnerabilities in recent history was found: HeartBleed. The popular open source cryptographic software library OpenSSL, had a critical flaw, [1] in the implementation of a extension on the Transport Layer Security (TLS) protocol.

The wide use of OpenSSL on several services such as web, email, instant messaging (IM), even virtual private networks (VPNs), managed to affect 17% of all SSL servers, mostly half a million of trusted websites.

In this article, we will see how it works, in a simple yet technical language.

xkcd Heartbleed.

TLS Protocol brief explanation

TLS protocol aims to provide secure communications between servers and web browsers. Whenever you see in your web browser a green lock next to the url, it means you are visiting a secure website, indicating that your communication with the website is encrypted, specially designed to prevent eavesdropping and tampering.

Secure URL, Green lock sample.

TLS accomplishes that by encoding your data in a way that only the recipient knows how to decode it. If a third party is listening to the conversation, it will only see seemingly a random string of characters, not the actual message or content of your data.

From Beat to Bleed

The HearBeat extension was a change proposed by Dr. Seggelman in 2012, and the bug was fully disclosed on April 7, 2014, by independent researchers at Codenomicon and Google Security. According to the RFC-6520, it’s a new extension implemented over TLS/DTLS, which provides a way to perform a keep-alive functionally.

Basically, a device sends an echo with a message to be replied back with the same information, just to make sure if the other device is still alive. If any of them goes down during the transaction, the other will know it by using this HearBeat mechanism, [2].

So, for example, you are reading this article, but you haven’t done anything in a while, your web browser sends a message to the server saying "Hello - Repeat it back to me", the server receive it and send it back to your browser.

The bleeding flaw

Researchers found that if a request made had a bigger length than what was sent on the message, extra information could be leaked at the response sent back.

For example, the web browser sends the following message:

"Hello - Repeat it back to me (28 kB)"

But the length of the request is modified to 40 kB, then it becomes:

"Hello - Repeat it back to me (40 kB)"

Then the message is sent and the recipient device gets a message with a length of 40 kB.

But the message was supposed to be 28 kB long, what about the remaining 12 kB? The recipient machine allocates in memory buffer those extra 12 kB of data and send back 28 kB of the actual message plus extra 12 kB of whatever is stored in RAM. Practically, you get more than the beat, instead, you can actually make it bleed, literally.

Bad luck.

Why? You may ask. The message can be up to 64 kB, not a lot of information leaked though, just 65536 characters taken from no other place than RAM, but it’s not like if an attacker could control which portion of the RAM wants, it just get whatever the machine grabs in the subsequent block of memory.

But that doesn’t seem to be harmful, probably no more than random data being sent, what’s the chance it can get something of real value? What if I told you an attacker doesn’t have any limit to send HeartBeats? It can stay all day long sending requests analyzing each 64 kB sent back and forth, and suddenly, the flaw could yield some, if not all of the following:

SSLprivate keys.Usernames and passwords that are submitted to applications and services running on the server.

Session tokensandcookievalues.

The worst of this vulnerability, is that there’s no way to trace it, records for this kind of activity aren’t logged by the OpenSSL daemon. Plus it’s not a client-server vulnerability, as malicious servers were able to exploit it on clients using the vulnerable version of OpenSSL, called a Reversed HeartBleed's.

xkcd Heartbleed explanation.

What caused the bug?

This is a portion of the code of the OpenSSL library - v1.0.1f (the vulnerable version). This fragment contains the bug and I’m gonna break it in the essentials details.

Here is a fragment of the t1_lib.c from OpenSSL.

The line responsible for the vulnerability is this one:

Looking at the documentation of memcpy, we see the following:

memcpy function.

The terms in parentheses behave like this: bp is the destination of the memory copied from pl, pl is the source of that memory and payload is the length of it, basically, the last one says how large is the data.

If payload states that pl is of 64 kB, when it really is of 0 kB we got a huge problem, because bp will be created with the same size as pl, filled of garbage data, but then none of that data at bp gets overwritten, because pl is empty or isn’t large enough to fill it.

The flaw on the code is that the length of the data wasn’t being validated, there were a missing bounds check before memcpy was performed. We’ll see that in the following lines of code:

The previous three lines of code just write the length of p, the '`HeartBeat` request', into the variable payload, the expected length of the payload. But notice there’s nothing checking if the expected length of the message corresponds to the actual length of the '`HeartBeat` request'.

The next line is responsible to set the length of the response back, the payload variable holds the expected length of the payload, thus that length will be written into the bp variable.

Now, the line containing the vulnerability explained before, takes a little more sense, pl could have a length of 5 kB, but payload gets a value of 64 kB, as it is not checked, bp variable will allocate in memory those 64 kB and send it just back, [2].

The fix

The vulnerability is only present in versions 1.0.1 until 1.0.1f and 1.0.2-beta until 1.0.2-beta1 releases. A few days after the incident a patch was released, the OpenSSL versions 1.0.1g and 1.0.2-beta2, got rid of the flaw.

The patch is essentially a bounds check, to validate the actual length of the payload.

The fully code patched can be seen here in this git diff.

This kind of vulnerability is named buffer over-read, [3]. For example, in the Heartbleed case, the program tries to read data from memory, but due to no bounds check, it tries to read adjacent memory, creating a special case of memory safety violation.

That was all?

Yes! That single line you saw there was the demonic 'call of Cthulhu'.

Nah, not really like that, but it tempted to wreak havoc, several companies like Amazon, SoundCloud, BitBucket, Github, the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA), almost 78 devices from Cisco Systems, Hewlett-Packard, even operating systems shipped with it, like Debian Wheezy, CentOS 6.5, Ubuntu 12.04.4 LTS, and a big etcetera had to shut online their services, warn or log out every user and inform them to update their password, there were even possible cases of the bug exploited.

Yet, despite 4 years have passed, there’s a high chance that a lot of services are unpatched against HeartBleed, since there are plenty reports from 2017 showing that at least 200,000 services are still affected.

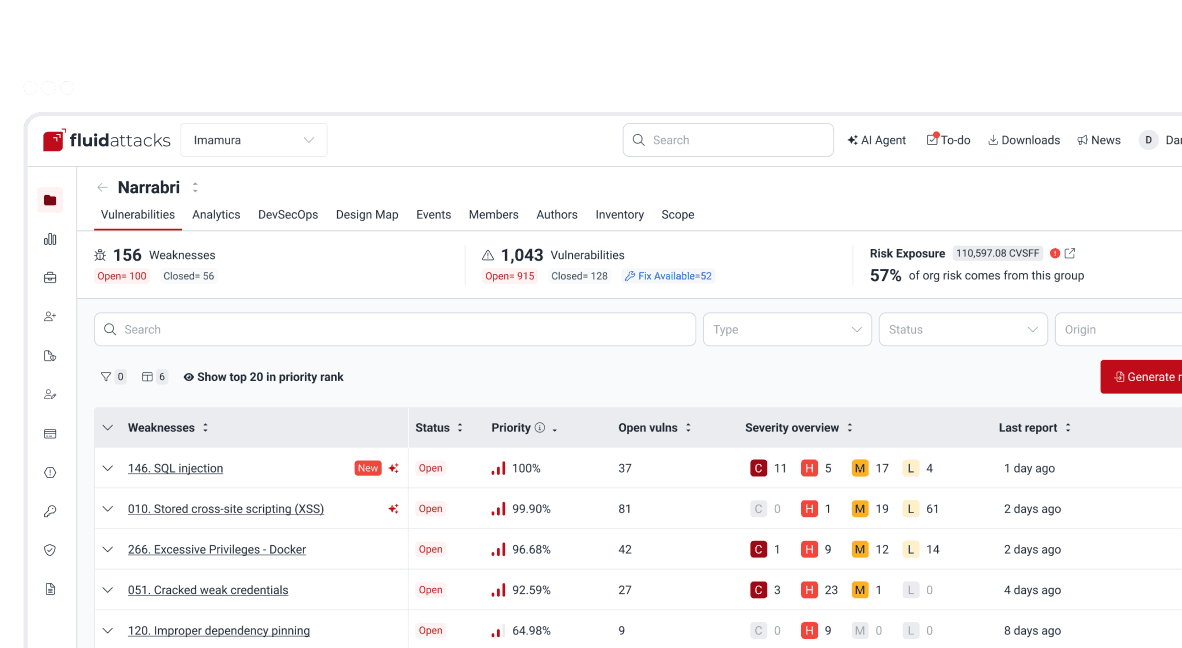

We at Fluid Attacks offer software composition analysis to find vulnerable software components in our clients' systems. Our clients can then manage these vulnerabilities in our platform.

References

IBM (2014). A technical view of the OpenSSL HeartBleed vulnerability.

Get started with Fluid Attacks' RBVM solution right now

Other posts