Attacks

Bypassing SQLi filters manually

Security analyst

Updated

May 20, 2020

8 min

Among the most recurring vulnerabilities are injection flaws, not for nothing they are first in the OWASP Top Ten list. This type of vulnerability can disrupt your entire security and infrastructure; almost any input can be an injection vector and all must be controlled. Here, SQL injection plays a big role, not only because of the risk of information leakage but also because it can lead to remote command execution or access to the internal network.

This vulnerability works when an attacker injects code into the queries that the application makes to the database interfering with its normal operation. This happens because the developers did not validate data input properly and did not apply the best practices to retrieve data from the database. Let me give you an example; imagine this piece of code:

Common SQLi vulnerable code.

Here I created a common login page code that checks the username and password. The variables are introduced through a POST request, and there is no input validation. An attacker could simply put the well known SQLi payload 1' or '1'='1 and bypass the login form. But if I filter some characters like the OR keyword or the single quote character, then will it be ok? Not so much.

SQLi Bypass lab

To set up our lab, we are going to use Hashicorp’s Vagrant; the source files are below. Create a folder with the name SQLi and save the Vagrantfile there.

setting up the lab.

Vagrantfile.

Then run the environment using

vagrant up.

This will create a Linux machine with LAMP installed and configured. At this point, everything we need has been completed and is ready to launch an attack.

Now we can set up our attacking machine. Here we are using Kali Linux with Vagrant too, but you can use whatever OS you prefer.

These are the tools that we are going to use:

If you are using Kali, then everything has already been installed by default.

We are ready to go.

Enumerating our server

First, we need to check the server ports. We can use nmap or ncat to do it.

port scanning.

nmap output.

nc.

Our server runs Apache on port 80. Then using Dirbuster, we can search for directories on the web server.

dirbuster.

As we can see, there is an admin site to which we do not have access and a normal site where our test cases are.

SQLi bypass attacks

There are three test cases; the first one is the simplest. It filters the OR|AND keywords and also the space character.

First SQLi filter.

The username is not injectable because it uses a prepared statement (this was intended to show the correct way of doing queries). If we put any of those characters into the query, it should respond with a Wrong alert.

To bypass this, we need to substitute those keywords: the OR keyword with the double pipe character ||, and the AND keyword with the double ampersand character &&. In this case, we need to URL encode it because of the content type of the web application resulting in %26%26. Finally, the space character can be bypassed using several substitutions, such as the following:

The block comment

/**/The ascii

%09horizontal tab characterThe ascii

%0anew line characterThe ascii

%0bvertical tab characterThe ascii

%0cnew page characterThe ascii

%0dcarriage return character

So, our well-known SQLi payload will change to something like '/**/||/**/1=1#

first bypass.

The next test case is a little trickier, it filters the same characters as before plus the single quote character. Also, it removes the use of the prepared statement in the username variable but validates the single quote character too.

Second SQLi filter.

So, what can we do to bypass this? The backslash character \ is a special escape character used to indicate other special characters in strings. This is useful in our case because if we inject that character into the username input, then the single quote character next to it will act as a literal one, and the username string will end next to the password input:

Backslash example.

It’s just a matter of injecting our code there; the payload in the username will be \, and in the password field it will be /**/||/**/1=1/**/--

second bypass.

The last example combines everything and adds more filters to the code; it is a different type of vulnerability because we are going to bypass the filter into an ORDER BY keyword.

Third SQLi filter.

Here we can hardly use any keywords or functions, and the union select won’t work either. To collect data from the database from an ORDER BY keyword, we need to use an error-based SQLi or a time-based one.

So, the first injection will be for testing the vulnerability, let’s inject a simple error-based SQLi where, if it is true, then it will order the items using the id, and if it is false, it will order them using the name:

?by=if(false,id,name)?by=if(true,id,name)

Now, let’s add another layer. We want to get information out of this and in order to do that we need to make some queries. In this example, we will get the guest password (if you want to get the admin password, you should try it yourself). Because the characters =, single and double quotes are filtered, we need another way to get the information of the user that we want. Here we have the IN operator and the CHAR function. The IN operator allows us to specify multiple values in a WHERE clause but we can use only one if we want it, and the CHAR function returns the ASCII character based on a number. Using both elements, a query for the guest password will be something like this:

guest password query.

Here the string guest is the combination of 103,117,101,115,116 ASCII characters. Now the MID function will help us to strip characters from that query and get the password character by character. This query will get the first character of the password:

guest password character.

Next, we need to compare it against another character; here we are going to use IN and CHAR again:

guest password comparison.

Finally, we put our query into the previous IF function and replace the spaces with the block comment:

guest password comparison.

With this, we can get the guest password using the ORDER BY function. Doing this manually would take quite a while, let’s automatize it using Python. The first thing that we need is a function that makes our queries and returns the response:

make request function.

Then we need to iterate through each element of the password and each ASCII character:

iterative query.

And finally, we check whether the list is ordered by id:

iterative query.

That’s it, create the exploit, execute it, and wait for the result. This could be done using any other query, for example, getting the MySQL user password hash.

Solution

The first thing that someone with this problem needs to do is to implement prepared statements; there is no way out of it. Injections can occur at almost any (if not all) database provider. With these statements, the software will present a robust data querying and discard the use of dynamic queries.

The next step is to execute whitelists to validate user input. When the developers use blacklist filtering, as in the examples above, there is a risk of missing some parameter that can allow the injection. Whitelists are a better approach because they only allow what is in them and nothing else.

Finally, there is the implementation of the principle of least privilege. I’ve encountered several databases executing queries using the root user; it is better to use limited users in our applications because it limits the range of action of the attackers that, in the worst scenario, get access to the database.

If you want more information about protections against SQLi, you can check OWASP or our Criteria.

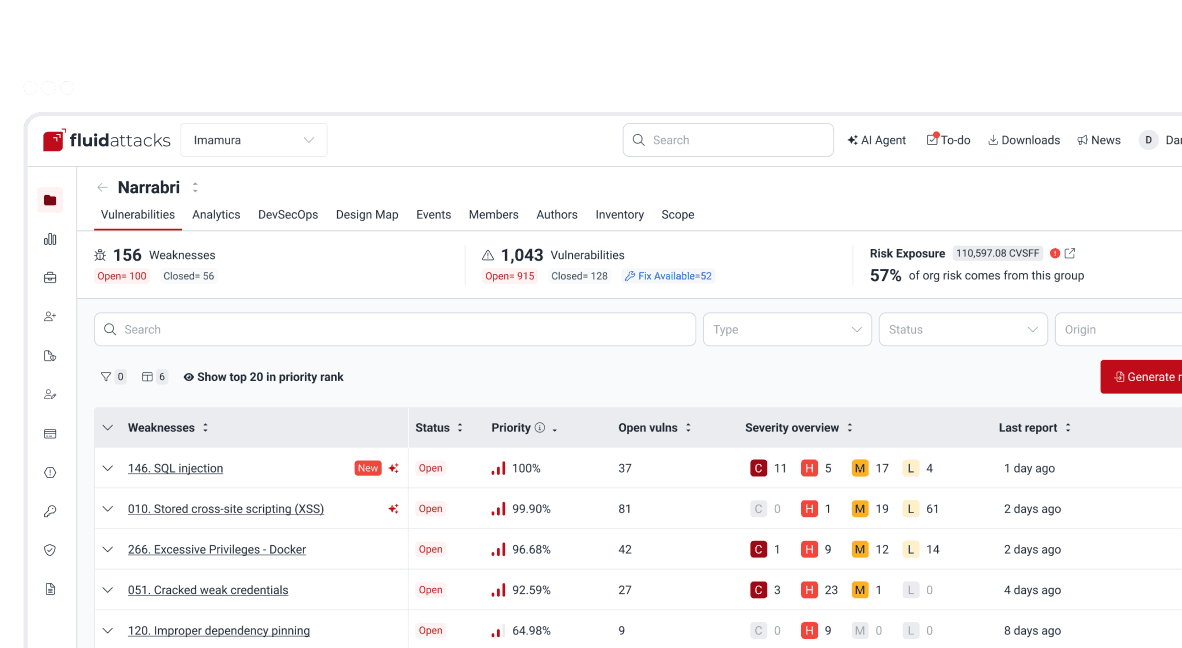

Get started with Fluid Attacks' ASPM solution right now

Other posts