Philosophy

Will machines raplace us? Automatic detection vs. manual detection

Security developer

Updated

Feb 13, 2018

5 min

More than 20 years have passed since Garry Kasparov, the chess world champion, was defeated by Deep Blue, the supercomputer designed by IBM. For many people, that event was proof that machines had managed to exceed human intelligence. This belief raised many doubts and concerns regarding technological advances, which went from workers worried about their jobs to people imagining that the apocalypse was coming (an idea encouraged by Hollywood).

All fiction aside, that first concern was well-founded and made some sense. Every year we witness new machines on the market with the ability to complete tasks with precision and speed and outperform dozens of experienced workers. By machine, I don’t mean a robot looking like Arnold Schwarzenegger in The Terminator. It could be any device programmed to complete a specific task, for example, self-driving cars, robotic arms and tools to detect vulnerabilities in web apps. As cybersecurity specialists, what can we expect from all this? Are we becoming increasingly expendable?

The inevitable outcome that Hollywood shows us.

Fortunately, our future does not look so bleak. Even though there are many powerful automated tools for vulnerability detection, the human role is still vital if a detailed and effective security analysis is desired. There are still situations in which we have the upper hand:

Tools may have large vulnerability databases. They can know how to find security flaws and what risk levels they represent. However, they do not have that human factor that comes with experience and allows a security analyst to identify which vulnerabilities can be combined to create a more critical attack vector. Expertise can enable a person to find vulnerabilities that a machine may overlook

Analyzers generate reports with all their findings and criticality, but how complete are they? They tell you how many input fields are affected by a vulnerability, but do they tell you which inputs allow sensitive data extraction? Do they tell you how to exploit a form to modify a database? Unfortunately, the answer is no. Automated tools only determine the existence of flaws. How those flaws can be exploited and leveraged to an attacker’s advantage is strictly a human skill.

A false positive is the report of the discovery of a vulnerability that does not actually exist. It’s a common problem among these tools, resulting from the inability to exploit a given flaw. A tool that does not adequately filter out false positives can do more harm than good. If you use it to avoid the cost of hiring a security professional, you may have no idea which of the vulnerabilities it reports are false positives. The task of filtering them may then fall to the developer, who may not necessarily be security savvy.

False positives are also one of the reasons why these tools are not commonly used in Continuous Integration environments. If we program an integrator to check every change made to a source code and stop the application deployment if an error is found, false positives could make those deployments a headache.

Netsparker (developer of one of these tools) agrees with this position: no analyzer can detect all vulnerabilities classified as the Top 10 most critical. They conclude that an analyzer cannot determine whether an application is functioning as intended and aligned with business objectives, or whether sensitive information (which varies by business type) is properly protected, or whether user privileges are correctly assigned. In these and many other cases, human reasoning must make the final decision.

Our goal is not to take merit away from these tools. We use many of them in our professional life, and they are powerful allies. What we want is to revise the mistaken belief that they are sufficient to decide whether a web app is secure or not.

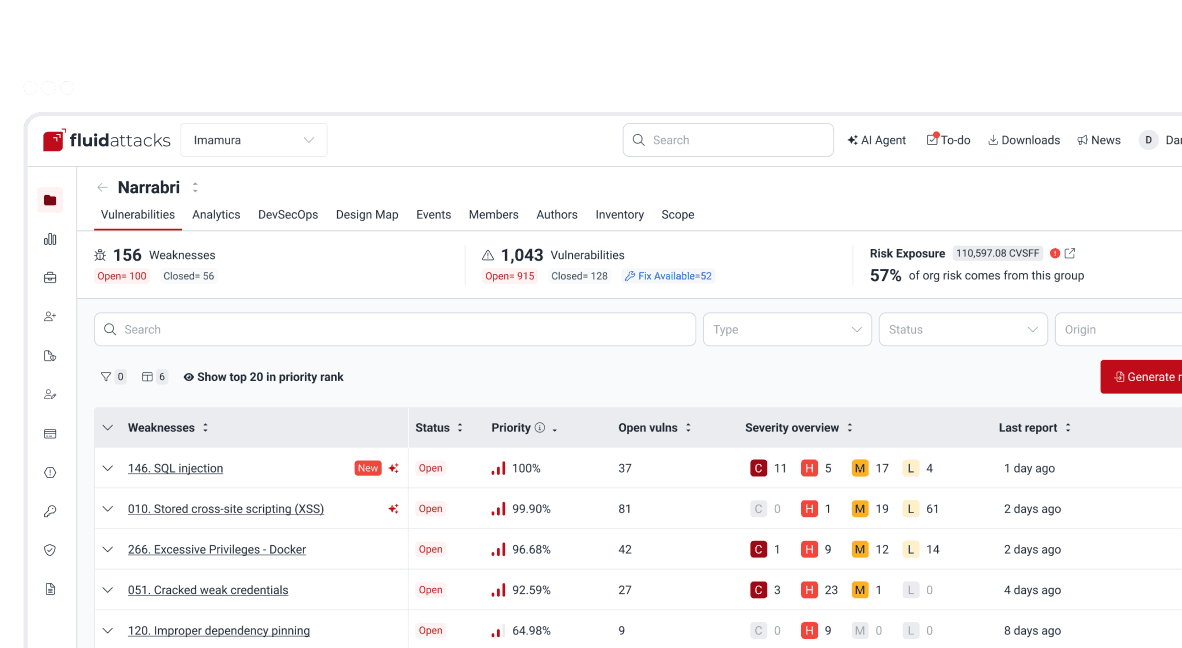

To do this, we developed an experiment. We used the insecure web application bWAPP and the automated analyzers W3af, Wapiti and OWASP ZAP. All of them share the features of being open source and able to be executed from the command line. Thanks to this, it is possible to use them in a Continuous Integration environment. For bWAPP, we assumed a total of 170 vulnerabilities, based on the company that developed the app. Let’s see how our contestants performed:

Table 1. bWAPP Vulnerability Analysis

Tool | Detected | % Not Detected | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

W3af | 28 | 83.5% | 00:02:30 |

Wapiti | 26 | 84.7% | 00:02:00 |

ZAP-Short | 42 | 75.3% | 00:19:00 |

ZAP-Full | 59 | 65.3% | 01:30:00 |

ZAP-Short refers to the ZAP tool with only the XSS and SQLi plugins enabled. ZAP-Full refers to the same tool with all of its plugins enabled. It’s important to note that the application authentication had to be disabled. We did this to allow the tools to work properly from the command line. This fact took the experiment further away from reality and left a layer of the web app unanalyzed.

Another important detail is that the analyzers were not targeted at the main site, as a real test would do. The target of the attack was a specific bWAPP page where links to all other pages are listed —this way, the tool achieves complete identification. bWAPP uses forms to reach all other pages, so targeting the attack at the main page would result in 0 sites of interest being found. Tools such as Burp solve this problem by evaluating the forms, but others fail in the same situation due to their inability to navigate the main site.

To facilitate the analysis of the results, let’s take the best (by ZAP-Full) and the worst (by Wapiti) and compare them against the whole surface of the application. Let’s see what coverage was achieved.

Visual representation of the best and worst results.

We can see that even the best of the tools we used left out more than half of the vulnerabilities, and false positives may exist among those it found. In addition, it took an hour and a half to finish the analysis, a time that is not appropriate for a Continuous Integration environment.

Companies wishing to reduce costs by avoiding hiring security analysts, relying solely on automated tools, would remediate vulnerabilities and gain a false sense of security. They would ignore the fact that more than half of the flaws could still be present to be exploited by malicious users. In this way, the resources saved during development would be spent, with interest, at the production stage.

Conclusions

Yes, the rivalry between humans and machines has been present for a long time now, and it will remain that way for a lot more. However, it is not necessary to see this as a rivalry in all aspects. For example, in the field of cybersecurity, it can be a complementary relationship, where the tools help the analysts perform repetitive tasks faster, and the analysts add their instinct and experience to detect the maximum amount of vulnerabilities efficiently.

Paraphrasing Kasparov in his TED talk, the relationship between humans and machines, through an effective process, is the perfect recipe to achieve our grandest dreams.

Get started with Fluid Attacks' application security solution right now

Other posts