| 5 min read

In July this year, I wrote a post based on the book Tribe of Hackers Red Team by Marcus J. Carey and Jennifer Jin (2019). On that occasion, I presented a short description of the book, which is primarily aimed at all those interested in red teams (Fluid Attacks, for example, is a red team). Additionally, I referred to Marcus's answers to the questions that he and Jin then addressed to the more than 40 experts that appear in their book. For this post, I will focus on what was shared by one of those red team experts. I hope it will be of your interest —bear in mind the meaningful value other people's experiences will always have for our learning.

In this case, we have the American-Canadian engineer Benjamin Donnelly, who "has worked as part of teams hacking such things as prisons, power plants, multinationals, and even entire states." He has participated in research projects like the DARPA-funded Active Defense Harbinger Distribution (ADHD) and was the Ball and Chain cryptosystem's creator.

Ben got closer to the world of red teams when, being in high school, he participated in a competition of the US cyber education program CyberPatriot. Although his training there was more geared towards the blue team's work, he managed to move into the "red arts" and began participating in NetWars tournaments. There, competing against professionals, Ben began to gain recognition for his skills and even succeeded in getting a job with a SANS instructor. After that, and certainly through hard work, he obtained the official job title of penetration tester/security researcher.

For those hoping to be eager beavers on red teams

Benjamin gives some recommendations to get a job in a red team. What he initially suggests is to recognize subtle differences between companies that perform this kind of work. Therefore he separates them into two groups, and for each case, he offers some advice.

Ben refers to the first group as "the computer network operator-type team," which focuses on exploiting networks or systems through diverse frameworks and hacking tools. The ways in which the attackers can gain and leverage access are then reported to the client. Accordingly, Benjamin comments: "If you want to join one of these teams, you need to be focusing on training on breach simulation because that’s what their world is all about." Indeed, at Fluid Attacks breach and attack simulation is part of our job. Moreover, Ben says that you don’t usually need lots of certificates for a job like this, and you don’t even have to possess college degrees if you have enough skills and make yourself known. Such is the case for working with us as an ethical hacker or pentester, for example.

Ben refers to the second group as "the security engineering-type team." According to him, they are focused on creating and auditing complex solutions to improve "the technical sophistication and security of a given software or hardware system." This team prioritizes system analysis from various perspectives and responds with the necessary controls to possible attack vectors that hackers might use on particular systems. And although I see this kind of work as more related to blue teams, I could also associate it with the position of IT security architects at Fluid Attacks. By the way, a university degree is not required in our company to apply for this job either. But as Ben says, for both groups, "you'll want some combination of computer science and information technology knowledge."

According to Ben, learning the necessary basic skills (e.g., manipulation of infrastructure) working in computer network defense positions will facilitate your transition to a job within a red team. "You’ll learn about what it is that attackers do as you learn to anticipate them." On the other hand, apart from the technical aspect, this young expert recommends working on some attitudes. He suggests keeping active the dispositions to ask questions, recognize without problems the ignorance on one or another subject, and correct oneself.

For those already sweating blood on red teams

From Ben’s perspective, the red team’s work is curiously more efficient when done individually. He refers to interpersonal communication as a big problem because this profession involves enormous amounts of information. Besides, the operations that are carried out are often very complex and highly specific. From his experience, Ben says: "We have to work out what’s happening inside [the system] by tracking huge numbers of variables indicated by external responses (such as error messages). Communicating exactly what is happening (and when) to each other can be a huge challenge."

However, Ben shows a strong interest in collaboration when working with blue teams and prefers the gray-box testing method instead of the black-box. (Nevertheless, the approach to be used regularly depends on what the organization you are working for chooses.) Ideally, for him, the analysts would be "testing discrete sections of the application/network to understand the threats posed to exactly that portion of the system independent of any other protective layers."

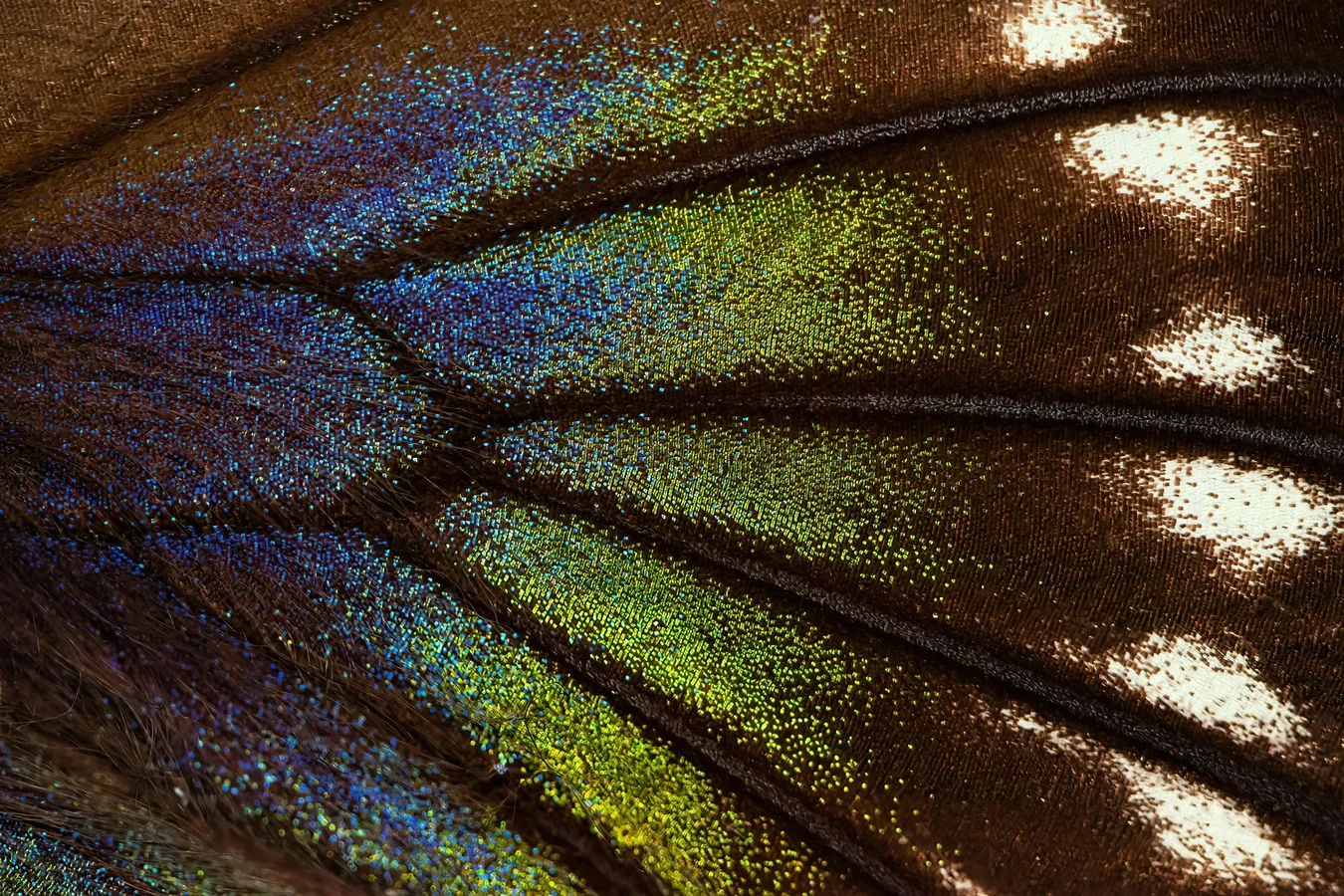

Benjamin’s original picture taken from pbs.twimg.com.

For Ben, red teams' members should not orient their work towards the I’m living a hacker’s life posture, desiring only to impress other people. This profession should have among its central objectives to help security teams optimize their systems' or software’s security. That’s why he says: "If questioned, I consider it my job to tell the product team literally everything I know. If they can hold all that knowledge, then I as a red cell professional need to move on and discover more." By the way, and as a fundamental aspect to take into account in the reports you have to make, Ben suggests the following: "Be detailed, correct, and honest."

For firms that in security aspire to be on the ball

When Ben is asked about the least effective security control currently in use, he seems to refer without hesitation to firewall technology. "All these expensive 'security' devices that seem to keep selling like hotcakes are effectively capable of stopping 0 percent of technically sophisticated adversaries." The biggest problem is that many people who choose to access such technology are unaware of its actual capabilities.

One of Ben’s most important recommendations in preventing attacks on systems or networks is "one hundred percent client (host) isolation." According to him, few companies currently in their networks require systems to communicate directly with each other. Cloud services have become especially relevant recently, and business applications do not have to live on-premises. The implementation of isolation helps enormously prevent attacks in which hackers could "gain access to and exploit your network resources." Ben concludes this part by saying: "Without device-to-device access, how am I supposed to find and exploit unpatched servers or workstations on your network? How am I supposed to pivot laterally? How am I supposed to relay credentials or access a rogue SMB shared directory?"

That’s all, folks!

All these were fairly simple yet worthwhile tips and ideas drawn from what Benjamin Donnelly shared on Tribe of Hackers Red Team. I hope you enjoyed them. If you'd like to know more about our red team at Fluid Attacks, please do not hesitate to contact us.

Recommended blog posts

You might be interested in the following related posts.