| 5 min read

In our last entry, we argued that fuzzing is both dumb and surprising. In this article, we’ll continue exploring the possibilities of fuzzing. This time though, we’ll focus on desktop application fuzzing, specifically UNIX applications written in C.

When developing in C, you usually have to handle memory issues

yourself. This makes your program very fast compared to languages like

Java. But at the same time this can lead to numerous kinds of

memory-access errors v.g. heap and stack

overflows.[1]

The woes of fuzzing

Recall that in our last article we ran a very simple-minded kind of fuzzing: give the fuzzer a list of inputs and it will invoke the program with each of those inputs one at a time. Since the list was very generic, only the most trivial inputs were successful; because it was not random at all, there could be no surprises.

Another type of fuzzing could be by injecting random inputs: this could lead nowhere, but it could show surprises, as we discussed in our last entry. Some go as far as saying that Heartbleed could have been found with fuzzing.

But blind, random fuzzing is usually very shallow, as was our attempted

SQL injection fuzzing. Such methods are ``very unlikely to reach

certain code paths in the tested code'' Amongst the attempts at solving

this problem we can count:

-

corpus distillation

-

program flow analysis

-

symbolic execution, and

-

static analysis.

However, while these methods appear to be very promising, they tend to be impractical in real use.[2]

Down the Rabbit-Hole

American Fuzzy Lop (AFL) is a

'security-oriented brute-force fuzzer' that tries to solve these issues

with 'compile-time instrumentation' and 'genetic algorithms'. But what

the heck does all that mean?

A different approach would be to make your fuzzer aware of the file

format taken by the tested program as input, but this is rather

inconvenient. Instead, what AFL does is, in plain words:

-

take the source code of your app,

-

compile it in a ``tricked'' way,

-

run it with a good input and then

-

iteratively modifying that input until you get an error.

For example, you might start AFL on a program with an image of a

rabbit as input. Then the fuzzer modifies the image a little piece at a

time, feeding it back to the tested program until a hang or crash or

other unexpected behavior happens. Here you can see the sequence of

images fed into the tested program:

Fuzzed AFL logo.

Via Wikimedia

Running AFL

The American Fuzzy Lop is primarily a white-box testing tool, so you

must have the code for the app you want to test. This is because AFL

needs to trick the app during compilation in a process known as

'instrumentation' so that it will allow the fuzzing process. Thus you

must compile using the included afl-gcc, which is a modified version

of the GNU Compiler Collection.

Then you should run your program with a valid, simple input: program input. If that goes well, put that input file in a folder by itself.

I’ll call it in. Make another empty one for the results called

out. I’m assuming everything lives in the folder you are in right now.

Now you’re ready to run AFL:

Invoking the AFL fuzzer.

afl-fuzz -i in -o out program input @@

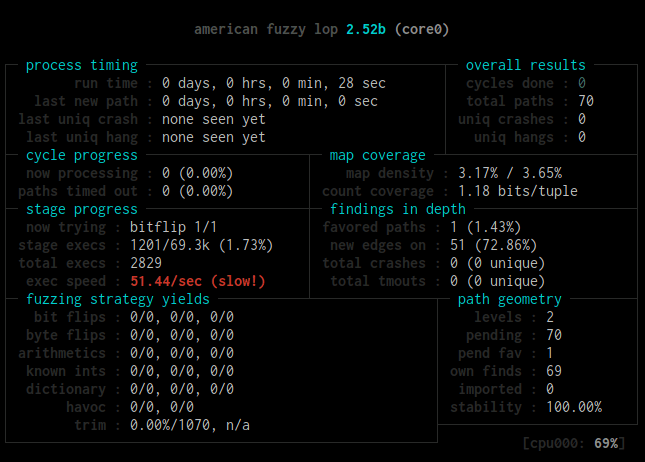

If everything went right, then you should see this:

AFL main interface.

Not very exciting, huh? But as long as the total paths indicator is

not stuck at 1, trust me, it’s doing its thing. AFL will continue

running until you tell it to stop by hitting <Ctrl-C>.

When last uniq crash or last uniq hang stops saying `none seen yet'', you have made your program crash. `AFL will save the inputs that provoked the crash in the output

folder we specified.

Fuzzing libpng - details

libpng is the official PNG reference library. If you’ve ever seen an

image in a web browser, you’ve been using it indirectly. It is used by

ghostscript, imagemagick, amongst many others.

As listed in its website, it

has had many bugs throughout its history. We’re interested in showing

here how to find

CVE-2015-8126

which is a potential pointer overflow/underflow, using American Fuzzy Lop (which is how they found it in the first place).

As it turns out, it’s not just a matter of following the generic instructions above, because if you do:

-

the fuzzer will tell you that the execution speed is slow

-

a single instance of

afl-fuzzon a single core will take a long time -

it won’t find anything anyway, because you need to patch

libpng -

you need the right executable using

libpng, namelyoptipng

So, let’s fix all these issues in the right order. Here the credit is due to Jakub Wilk who originally reported the bug.

-

Apply this patch to

pngrutil.ctolibpng-1.5.1 -

You need to instrument

libpngandoptipng-0.7.5usingafl-clanginstead of the defaultafl-gcc. Also installlibpngwithmake clean allso it doesn’t conflict with your local installation (which you most certainly have):CC="afl-clang" CXX="afl-clang``" ./configure --disable-shared make clean all CC="afl-clang" CXX="afl-clang``" ./configure -without-system-libpng make install -

To use all

ncores available to you, creatensubdirectories in your output folder. Runafl-fuzzas before with the option-M folder1for the first core, and-S folderxfor the rest. Example with two cores:afl-fuzz -i in -o out -M core0 program input @@ afl-fuzz -i in -o out -S core1 program input @@ -

Use a small

PNGfile as input, such asnot_kitty.pngincluded inAFL. -

You can further speed up the process by

`cheating'' using a previously produced set of fuzzed images available here. Put these images in your `outfolder.

Following the steps above, here is the optimized afl-fuzz running on

libpng and optipng with 4 cores:

AFL successful run

(click

to view larger).

We see that, within a few minutes, the slave processes have made the app

hang, but not the master. The reason falls out of the scope of the

article, though; see AFL performance

tips.

So what’s the bug?

OK, we made the application hang. So what? It’s not up to me to explain it, but I will quote the essentials from the pros for the sake of completeness.

Back then, if you called optipng with this

file

you’d crash it:

$ optipng crash.png

** Processing: crash.png

Warning: Can't read the input file or unexpected end of file

24x32 pixels, 1 bit/pixel, 4 colors in palette, interlaced

optipng: opngreduc.c:697: opng_reduce_palette_bits:

Assertion `src_bit_depth == dest_bit_depth' failed.

Aborted

The problem happens when an application uses low-bit-depth palette

mapped PNG data because when returning the palette it has to be copied

back to the OS-specific format in a potentially vulnerable way:

for (i=0; i<num_palette; ++i) {

bmh.palette[i][0] = tmp_palette[i].red;

bmh.palette[i][1] = tmp_palette[i].green;

bmh.palette[i][2] = tmp_palette[i].blue;

}

And here’s the problem with that code:

`This is valid code according to the `PNG spec because

num_palette cannot be more than 16 in a valid PNG. Unfortunately in

libpng before the fix num_palette can be up to 256 with an

appropriately modified PNG. The overwrite above is at the high address

end of bmh, so it overwrites up the stack (on a typical machine) into

the call frame and pretty much gives an attacker complete control over

the application program.'' [3]

This bug was actually found using AFL at the time on Debian Sid, as has

been the case for many other real-world C applications, even

high-profile ones like bash, the X server, curl, and the Linux kernel. See `AFL’s ``bug-o-rama trophy

case''.

So there you have it: as promised, a more in-depth follow-up to our initial invitation to fuzzing. According to `AFL’s father, this technique is both very powerful and underappreciated:

Fuzzing is one of the most powerful and proven strategies for identifying security issues in real-world software; it is responsible for the vast majority of remote code execution and privilege escalation bugs found to date in security-critical software.[2]

— Michal Zalewski

Hopefully this article has helped to spark some curiosity and convince you a little of that.

References

Recommended blog posts

You might be interested in the following related posts.